perception exercises

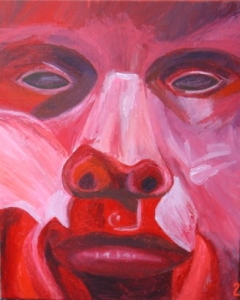

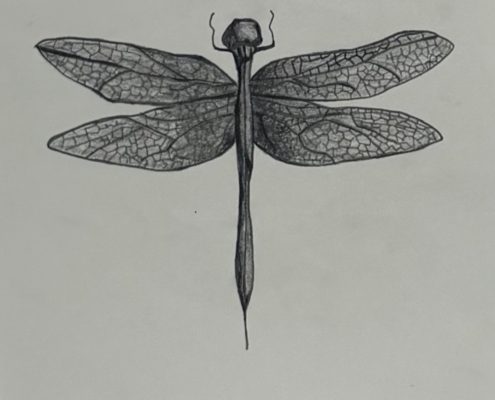

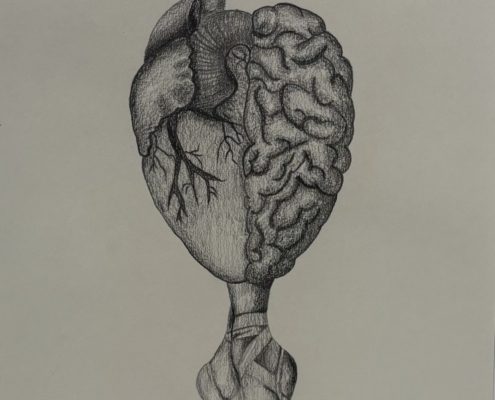

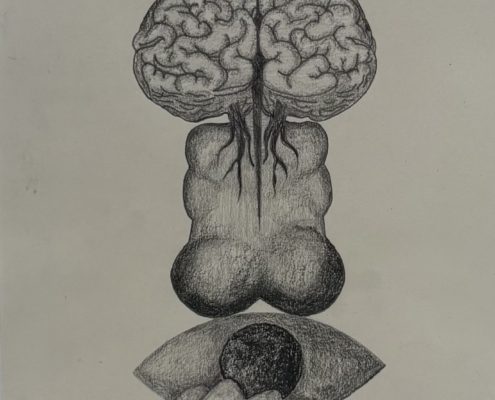

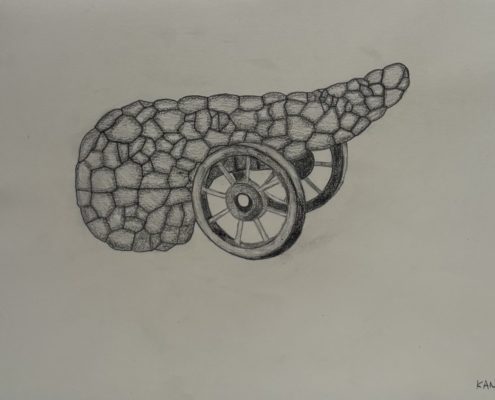

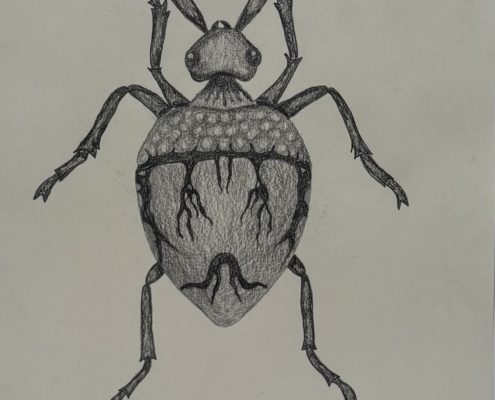

In Konstantinos Kantartzis’ solo exhibition Perception Exercises at Batagianni

Gallery, the viewer discovers forms which are mostly connected with vital human

organs and bones, insects, nuts, trees and other elements of nature. The title of the

exhibition emerges from the titles of the artworks, as they are called Perception

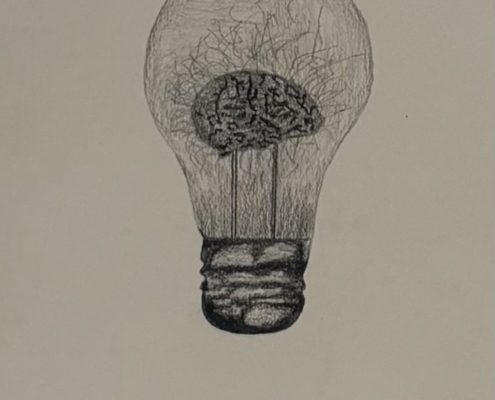

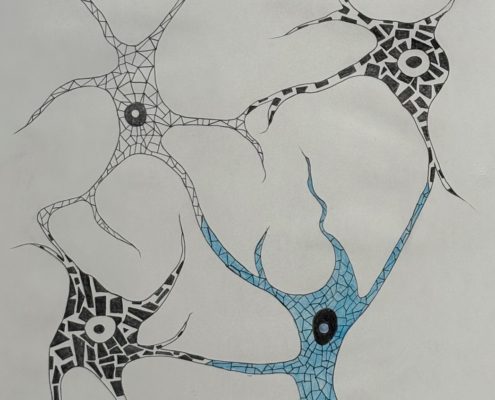

Exercise 1, Perception Exercise 2, etc. The core center of perception is the area of the

brain called Island of Reil (Insula). The Island of Reil is the most important part of the

brain regarding the gathering and processing of information that our senses collect

from the environment. The processing of all these information leads to the realization

of the state of our body and feelings, resulting in the development of empathy and the

conversion of thoughts and feelings to intentions and actions.1 Additionally,

Pareidolia, which is a type of perception, evolves in the Island of Reil. The term

comes from the ancient Greek words “para” (parallel, side by side) and “eidolon”

(idol, effigy and image) and was first used scientifically by the psychiatrist and

neurologist Klaus Conrad in 1958 in order to describe the psychological phenomenon

in which a random inconspicuous external stimulus/pattern can be perceived as

recognizable and significant. Pareidolia is a form of Apophenia, which is the tendency

of the brain to find meaningful connections in vague and meaningless data and

information (such as objects and ideas), derived from previous experiences.2

We come across the phenomenon of Pareidolia in artists of different periods in the

history of art. For example, in the “Treatise on Painting”, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 –

1519) argued that if we look at walls stained by dampness, we can discover

landscapes, remains, rocks, battles, strange forms and other images,3

a reference

highlighted by Rena Papaspyrou (b. 1938) as well, since herself focuses on the

“episodes” or the associative images that arise from the faint natural alterations on the

surfaces of her wall detachments. The Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526 –

1593) created illustrations of fruits, vegetables, books, human bodies, and other

objects in arrangements that form human portraits.4 Later, in the paintings of

Modernism, like those of Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890), Paul Cézanne (1839 –

1906) and Paul Gauguin (1848 – 1903), we can discover secondary images, created

consciously or subconsciously by the artists. Additionally, one of the main advocates

of Surrealism, the Spanish artist Salvador Dali focuses on the illustration of his

subconscious instincts, the desires and sexual fears that haunt him, inspired by the

psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud. He developed the technique of merging

portraits and landscapes in his sculptures, which we also find in many subsequent

artists. He introduced the “Paranoiac-Critical Method” in the 1930s, which is related

to Pareidolia and Apophenia, as Dali places paranoia in the service of creativity. 5

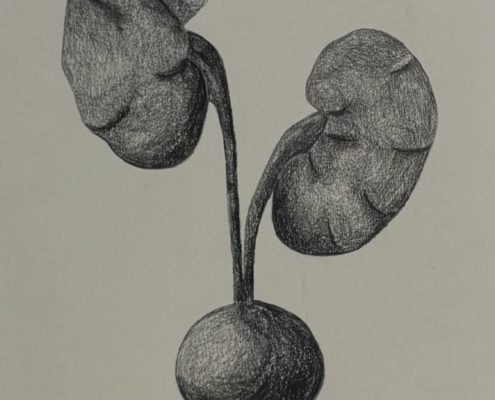

The Perception Exercises sound like a way of training to stimulate and enhance

perception, as Kantartzis almost obsessively produces a large number of works with

dedication and passion. With this “practice,” it is as if he is constantly attempting to

respond to the stimuli around him and with all his energy, he is trying to render what

he sees and perceives. For example, he has created a large number of ceramics in

different colors that refer to both walnuts and human brains, but he chooses a much

smaller number to exhibit. It is as if he is constantly and “frantically” experimenting

and turning himself into a production machine.

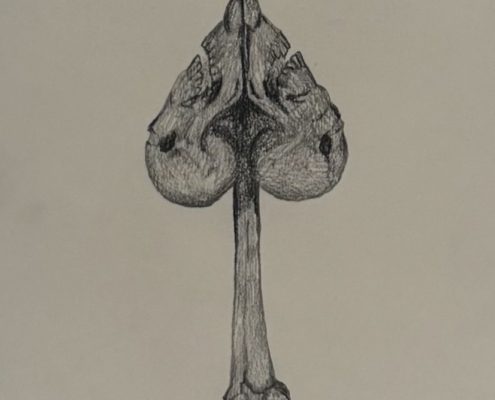

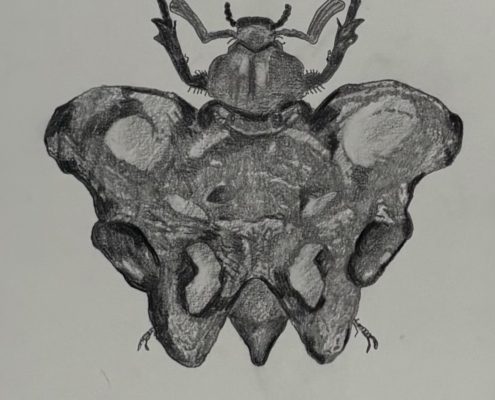

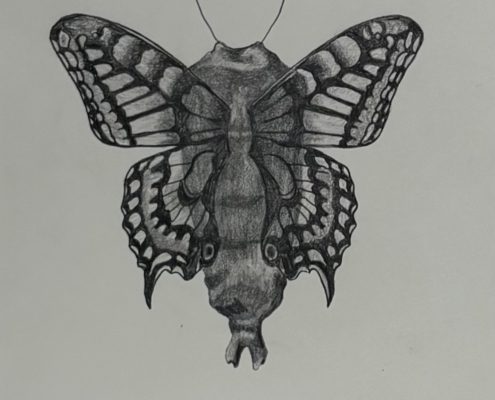

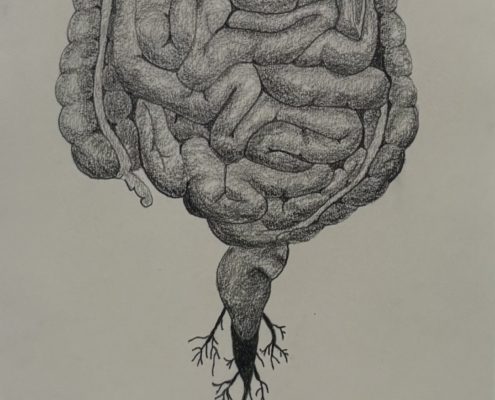

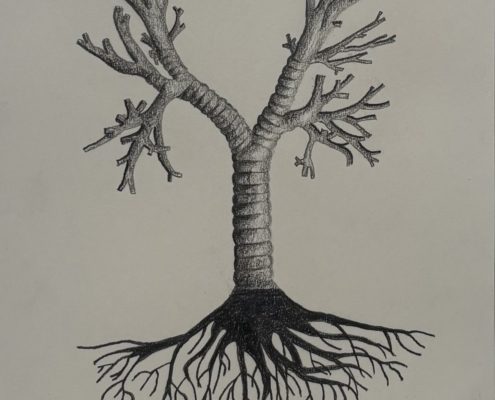

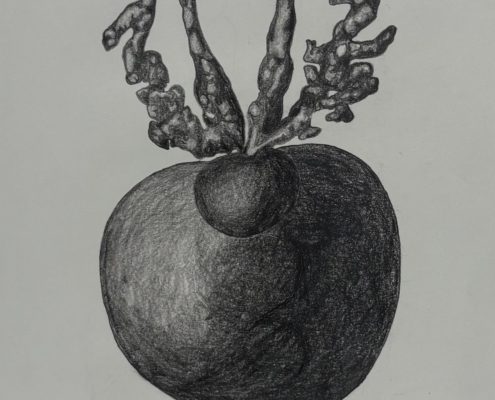

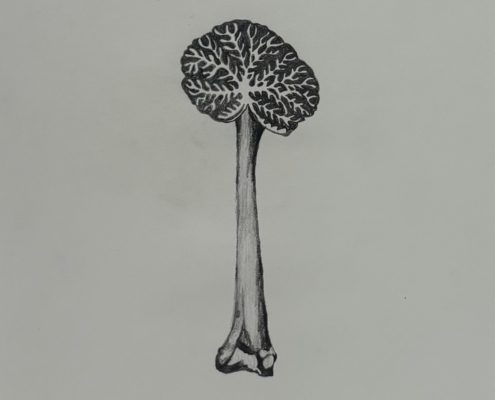

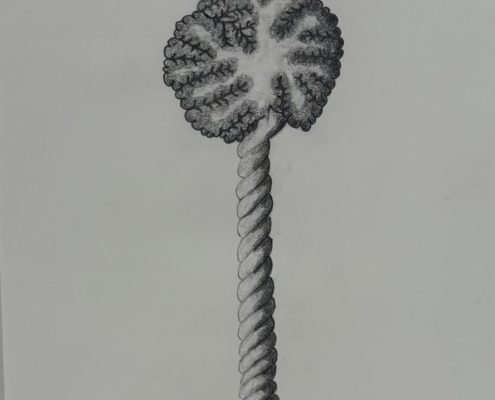

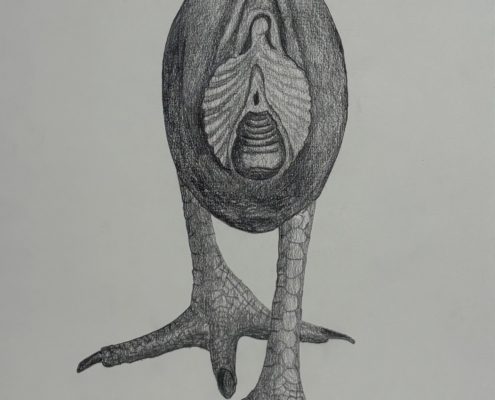

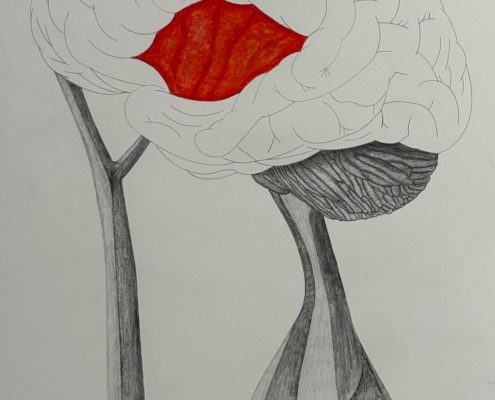

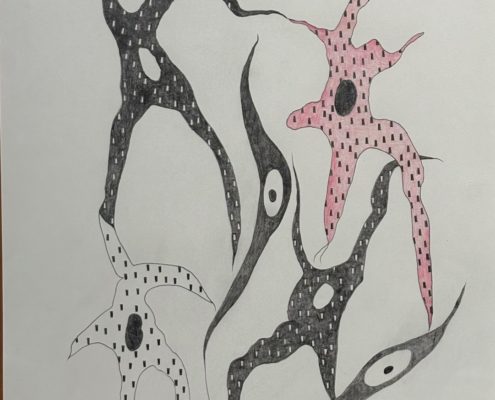

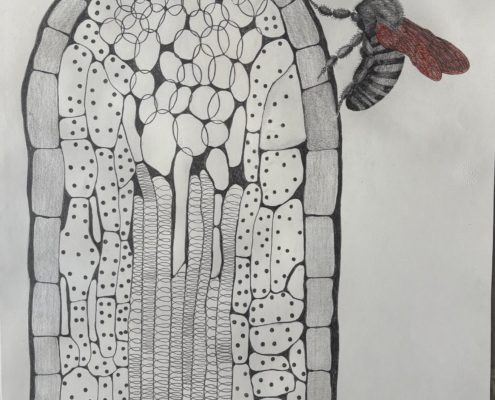

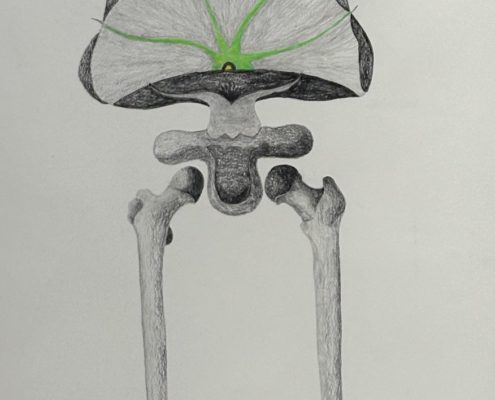

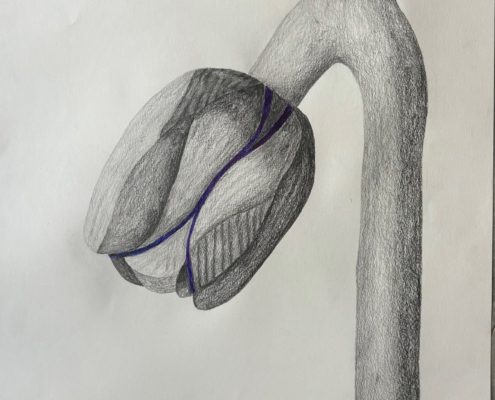

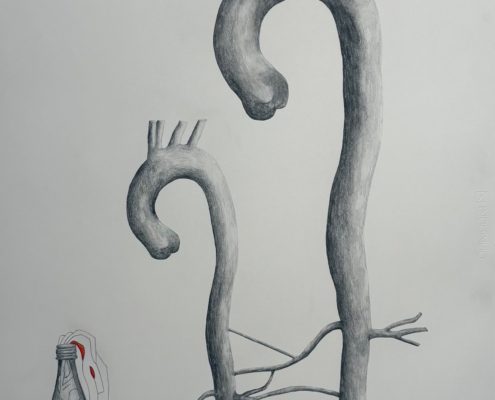

Through his works, Kantartzis points out that in life there are different aspects of

things. In some of his drawings and ceramic sculptures one can discover forms that

resemble trees or mushrooms and at the same time lungs. In them, Kantartzis

emphasizes the vital role that nature plays in human life, the inextricable connection

that exists between nature and the organism, a connection that is also visible, an

antithesis that highlights the importance but mainly the interdependence of the two.

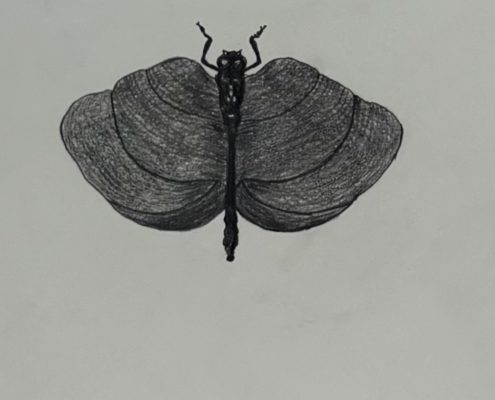

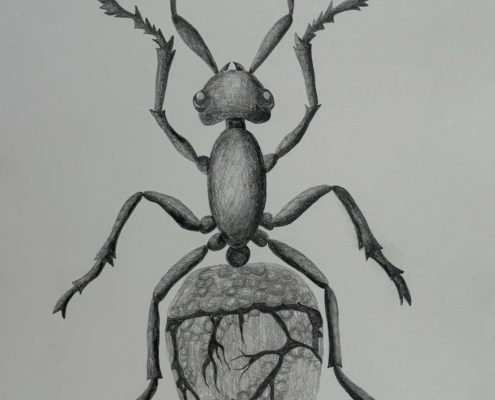

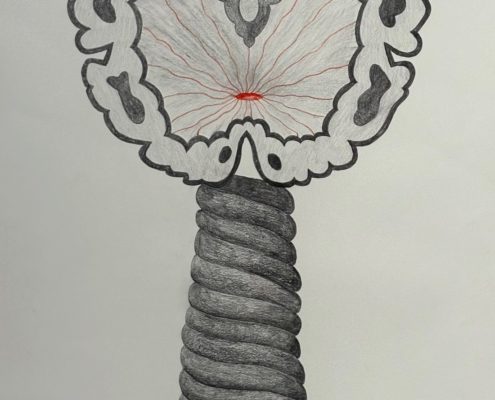

In one of his pencil drawings, we see at first glance a fly trapped in a spider’s web.

Looking more closely, we realize that a part of the fly’s body resembles a human

tongue. We understand the implication that when we do not control our tongue and let

it “run free” and say whatever it wants without responsibility, without “filtering,” we

can find ourselves trapped in a vicious cycle. A similar idea is expressed in his wall

piece, where a ceramic figure that refers to a human tongue or a snake’s head emerges

from an old-fashioned gold frame. On the one hand, the work is reminiscent of

Caravaggio’s (1571 – 1610) attempt to expand his figures out of the borders of

painting into space, on the other hand, it teaches us that speech is not always

experienced with detachment and can easily cross the limits and become poisonous.

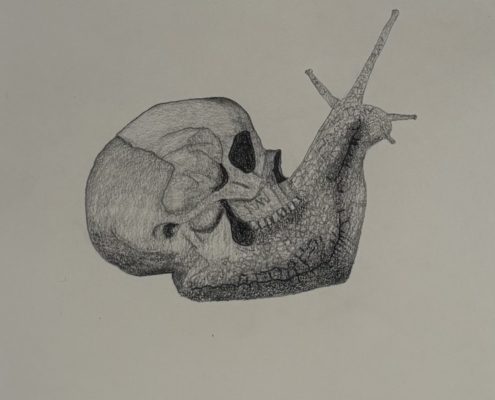

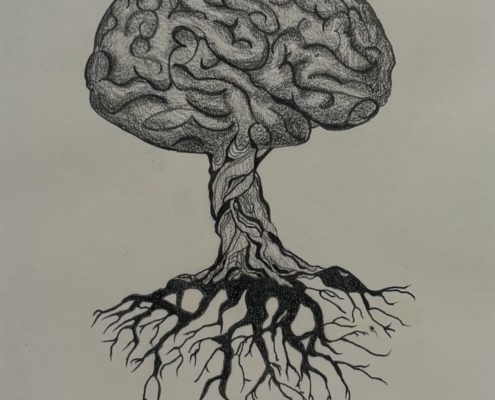

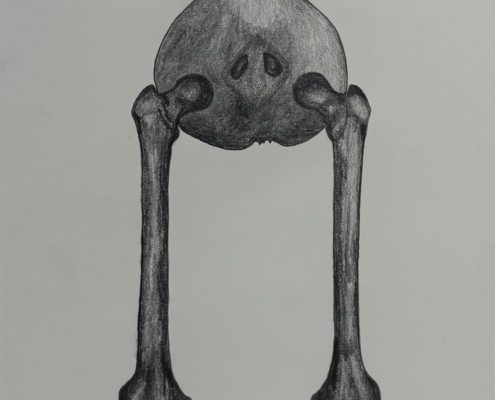

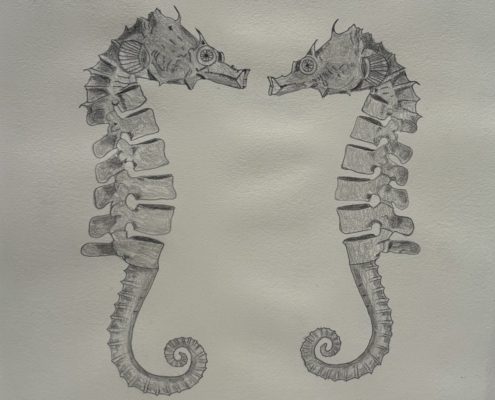

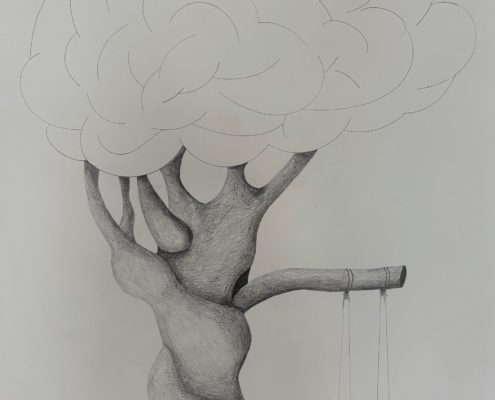

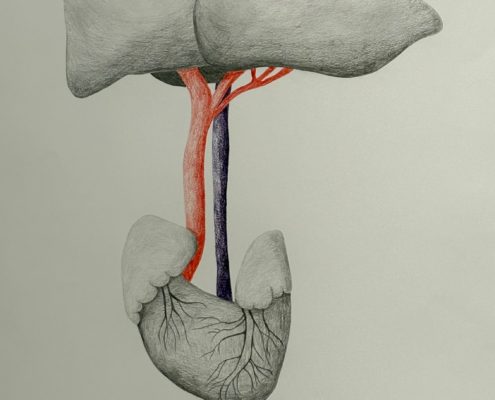

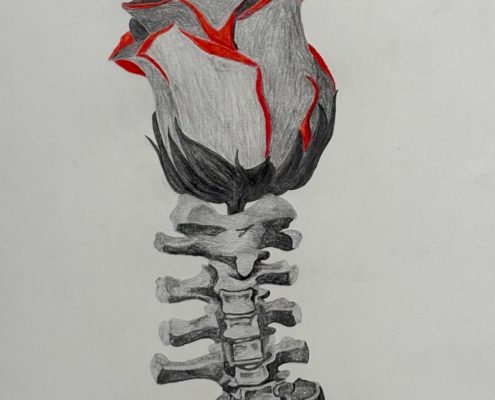

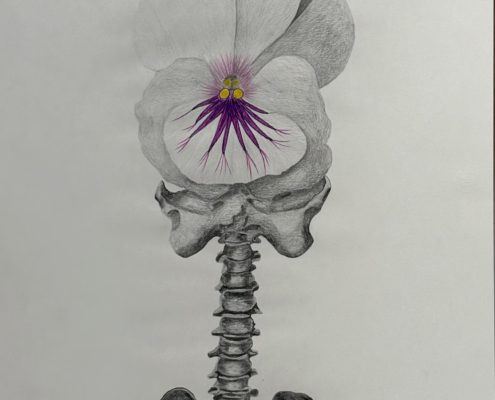

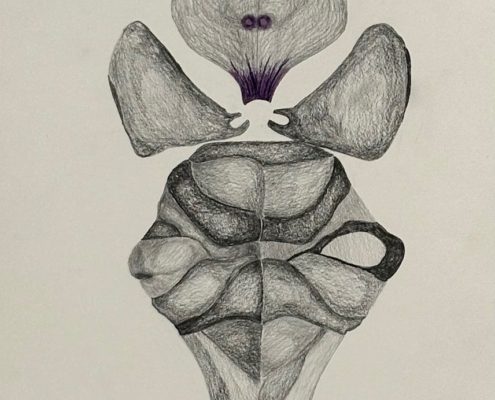

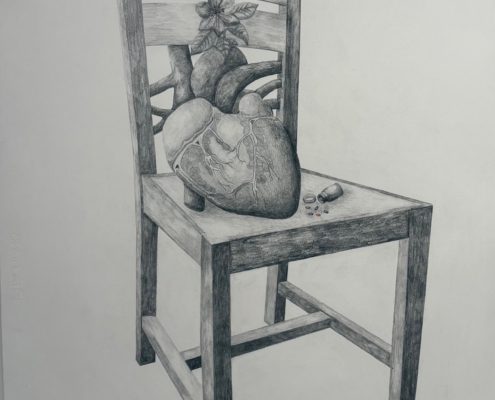

We realize that the human body is at the center of Kantartzis’ works, and especially

its non-visible side, what exists under the skin, such as the vertebrae, the lungs, and

the brain, perhaps due to his parallel capacity as Dermatologist-Venereologist. The

science of medicine offers him the ability to look beyond the flesh and extract legible

forms of the internal chaos of the human body. His forms, however, do not resemble

the brutality found in depictions of the anatomy of a corpse, as he is interested in

“playing” with the multiple readings that arise from the phenomenon of Pareidolia, as

is the case of the drawing with the tree/brain, where a child’s swing is tied to one of

the vessels (which supply blood to the brain/branches). Beyond the phenomenon of

Pareidolia, the empty swing implies the existence of the child and mainly the contact

that develops with the parent during play, as the latter pushes/touches the child on the

back to rock him. This contact conveys experience, emotion, security, confirmation,

with the final recipient being the brain.

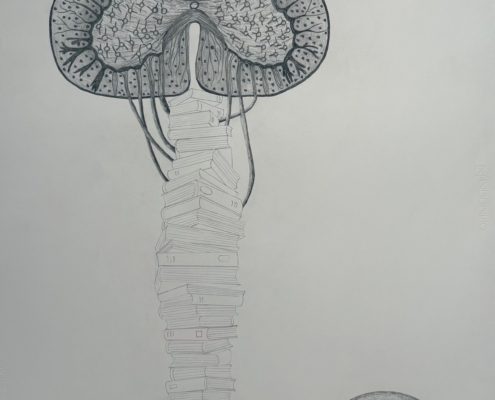

In the sculptural installation of two “tree trunks” made of ceramic pieces/vertebrae,

Kantartzis wishes to touch upon the relationship between parent and child and the

Oedipus complex. The large trunk symbolizes the parent and the smaller one the

child, while the metal tubes that emerge from the ceramics and connect them together

are reminiscent, on the one hand, of the neurons found in the vertebrae and, on the

other, of the complex bond between parent and child. Kantartzis transforms the

human body, and specifically the spine, from a simple object of research and personal

perception into a place of experience for viewers. Our mind, which is a set of

functions performed by the brain and shapes our perception of the external world,

determines our attention and actions. 6 Thus, we receive from the vertebrate trunks a

“signal” of both robustness and vulnerability at the same time, which guides our

movement, our exploration with curiosity but also caution around and among them.

Finally, the processing of meanings and images and the stimuli offered by the works

of art are based largely on the recipients themselves. Each of us reacts differently to a

work and we give our own interpretations, as our appreciation and perception is

influenced by our personal inclinations and prejudices, our cultural background and

taste. 7 Also, let us not forget that each project is completed with our perceptual and

emotional involvement, as we, the viewers, add meaning and value to the project

through our own interpretation and approach.8

In the case of Kantartzis’ work, we are

invited to discover the forms he has created through the phenomenon of pareidolia,

but at the same time to take with us our own impressions and make our personal

connections.

Stratis Pantazis

Curator and Art Historian